As a Black African woman, images of Sara Baartman haunt me.

The legacy of the subjugation and objectification of African Femmes starts in the material reality but reverberates temporally through the construction of photographs—an audible and palpable reverb, resonating through our ears and thumping deep within our bodies. A phenomenon defined by Tina Campt as a phonic substance in which the sound inherent to an image, one that defines or creates it, is neither contingent upon nor necessarily preceding it, not simply a sound played over, behind, or in relation to an image; one that emanates from the image itself. The sounds emanating from images of Sarah Baartman are hauntingly solitary, a subdued yet penetrating echo born from a life driven by the weight of the public's desires with no room for expression of her inner wild longings. There is a sharp focus on her body, while her eyes and face are blurry, steeped in black shadows. Within this blur, her eyes let us in on a glimpse of a woman's unmaking. The construction and dissemination of Baartman's image didn't end with her; it was weaponized to shape perceptions of race, class, and gender, ultimately reinforcing the structural dominance of whiteness.

And it is here that I realize what Tina Campt meant by: the structural dominance of whiteness is like a gravitational pull, a force that tethers our inner desires as Black women as things never to be expressed.

I think about my grandma.

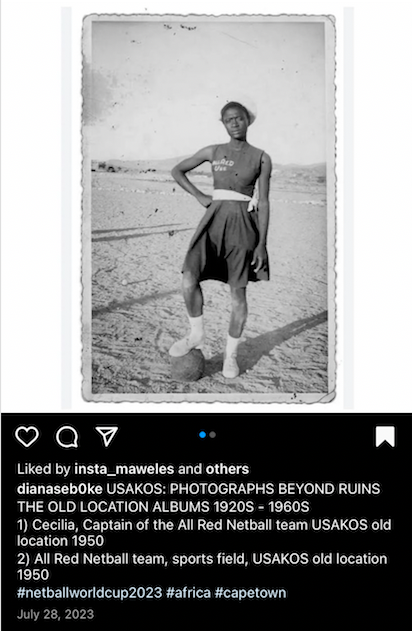

As a product of this generation, I turn to the internet to escape, spending hours scrolling through images, trying to decompress, make sense of things, and make sense of myself. During one of these scrolls, I came across a carousel image that was captioned: USAKOS: PHOTOGRAPHS BEYOND RUINS THE OLD LOCATION 1920's- 1960s. The first image in the carousel was of a woman wearing a uniform dress with a white belt tied tightly around her waist and her hair pinned back in a white scarf. Posing with one arm confidently resting on her waist, the other casually hanging by her side. Her foot is placed on top of a netball, suggesting an athletic prowess. Her gaze pierces through the lens, head tilted, brows furrowed, staring at the camera as if she knows she's the best athlete that you'll ever see in your life. The dirt that covers her knees and legs signals she just got done playing an intense game. In this image, the silhouettes of the people around her emanate the sound; I imagine it's the sound of cheering, chatter, and banter— the sound of life. The caption for this image reads Cecilia, Captain of the All Red Netball team USAKOS, old location 1950. The second image in the carousel shows the All-Red Netball team in action as one of the players skillfully shoots the ball into a towering net. Everyone on the team looks up at the ball in anticipation as the crowd comfortably watches the game from the sidelines. The second image caption reads All Red Netball team, sports field, USAKOS old location 1950.

Maybe it was the image of African women reclaiming their bodies through sport, or perhaps it was Cecilia's unapologetic stance. It was evident that these photographs pulsed with life. Witnessing them led me down a rabbit hole, where I discovered they were part of the 2015 exhibition Usakos – Photographs Beyond Ruins. The exhibition curated by Paul Grendon, Giorgio Miescher, Lorena Rizzo, and Tina Smith focused on a central Namibian town, Usakos, whose history is tied to the development of the South African Railway system. Development of a railway system brought prosperity to the city in the 1940s and 1950s, but it also attracted white foreigners who implemented an apartheid regime. Consequently, the African people were forced out of their homes and into racially and ethnically segregated townships on the city's outskirts. The curators took to analyzing the history of Usakos through the personal photo albums of four Namibian women: Cecilie //Geises, Olga 'Ollu'/Garoës, Gisela Pieters and Wilhelmine Katjimune.

In this instance, encountering African Femmes assuming the role of creators and collectors of their images through the photo album highlights how Black women on the continent have used aesthetic practices in meaningful, creative, pleasurable, and resistant ways. It provides a basis for us to examine the impacts and implications of their aesthetic practices on the more significant Black diasporic collective memory and reconceptualize notions of African femininity in the public sphere. It requires us to assume the position of a Black gaze in what Campt describes as shifting the optics of “looking at” to a politics of looking with, through, and alongside another. This notion forces us to suspend Western modes of thought about the archive, who is deemed the authority in authoring history, and how that authoring takes shape.

Photo albums speak to an individual's autonomy to construct how they view the world, what memories they hold on to, and what events they choose to forget. It's an alternative space that pushes against a dominant institutional archive and does what the dominant archive doesn't, which rightfully assumes subjectivity. It harnesses this subjectivity as evidence of a life that speaks to the experience of an existence entangled within these power structures and existing despite them. Within Eurocentric masculinist systems, aesthetics are pushed as something of purity, an aspect that represents the pinnacle of beauty, a euphemism for white supremacy. Like the archive, it is a realm solely meant to be observed and confirm the dominant worldview. On the counter, aesthetics often emerge as a generative work African femmes have mastered, existing in and alongside these structures not only for personal preservation but also for collective forwarding. To be generative, African Femme Aesthetics requires a level of utility as it becomes an indicator of the embrace of time; with time comes wisdom, and with time comes a harnessing of sensibility. Visible marks of adhesive tape, scratches, frayed edges, and pinholes stand as testaments of motion as photographs featured in the exhibition came from a hereditary lineage of being passed down from one woman to the next. Cecilie //Geises, Olga 'Ollu'/Garoës, Gisela Pieters, and Wilhelmine Katjimune harnessed their photo albums as tools of memory, using assemblages of texts, images of small objects, letters, photographs, notes, and personal documents to guide them in recalling and narrating the past. This indicates a necessity to tie their perception of images with sensory elements reflecting their sensibilities and experiences. These sensibilities extend to the way their photo albums were housed, with the women using shoeboxes, tin cans, handbags, and frames as vessels to store their images.

Pictorially, the images in their subject matter showed a recurrence of natural and architectural features in constructing an individual's portrait. Photographs would be taken in front of trees, sitting at tables and on chairs, engaging in leisure activities like sports, going to public social venues like cafes, and in the backyards of friends and family houses. Images spoke to the relationship between the photographed, the landscape, and the photographer, components coming together to discuss the individual's desire to self-publish.

At the District Six Museum, these words were used to articulate the conceptual framework of Usakos Photographs Beyond the Ruins. The museum expressed:

“These women's small but continuous daily aesthetic acts powerfully countered the ruination of their living environments. This is why the collections transcend the concern to recover the past alone and also describe an ongoing reflection of the present inviting an opening into the future"

My societal position as a Black African woman living in the west I continually grapple with the limits of the English language as words such as Aesthetics and its definition cease to encapsulate my lived understanding of them. For example, a quick Google definition of "aesthetic" pops up as concerned with beauty or the appreciation of beauty, or giving or designed to give pleasure through beauty, of pleasing appearance. However, as previously stated, beauty is often a standard weaponized by white supremacy, and Black women have often been used to create notions of the "other" or a metric to dictate what beauty is not. The realm in which I came to understand aesthetics was through spaces where I and other Black women shared intimacy — spaces of sanctity & an imaginative sense of untethered freedom. This included trips to the hair braiding shop and visits to the seamstress. It was within sisterhood, assisting each other in selecting outfits for events, through talking on the phone for hours; telling the most ridiculous stories, through watching films together, in playful moments within my mother's closet, and within the pages of her photo album, that aesthetics became tangible and meaningful to me.

It's an essence I try to theorize in my own work as an image maker, the essence of not only seeing yourself as a Black woman but encompasses the process of constructing one's sense of self through encounters with other Black women. This has caused me to personally reconceptualize the definition of Aesthetic through the lens of being a Black African Femme:

African Femme Aesthetic- By nature a (re)generative process that combines creativity and pleasure as an effort to manifest one’s inner presence outwardly. The daily act of individual desire becomes a transtemporal influence contributing to the cyclical process of mobilizing collective creative energy and communal morality.

Video clip from creating with my sister Lordina

Black women are under a persistent threat of our souls unmaking, images make sure that that unmaking doesn’t stop in one lifetime but clutches on to generations of Black women that come after. This is evident in the construction of Sarah Baartman and can be felt through the undercurrents of media portrayal of Black women fueled by misogynoir and anti-blackness. By no means were the contemplations and issues discussed in this paper exhaustive; rather, I hope to use them as the starting point to think about the ways aesthetics are used amongst Black women to resist this unmaking and become regenerative to themselves and to those to come. Usakos: Photographs Beyond the Ruins we witness how through African Femme Aesthetics the process of embodiment or locating oneself as an individual does not happen in isolation nor is it something to be understood objectively. It's an act practiced daily, it's proof of life in spite of the precarity we face everyday.

Wo Nuabaa,