Ushering a New Era of Imagination: Fatimah Tuggar Working Woman

The cultural context that informed Fatimah Tuggar to create Working Woman in 1997 was shaped by the infant stages of public internet access. With the internet launching four years prior in 1993, conversations about the digital divide between the West and the rest of the world began to emerge. Unsurprisingly, these discussions often replicated the same insular and regressive Western rhetoric surrounding Africa and its perceived "primitivism." Subsequently, this only reinforced outdated stereotypes restricting public views to narrow Western frameworks of knowledge and experience, thereby limiting understanding and engagement with technology and information sharing.

In chapter 1 of her book The Invention of Women: Making an African Sense of Western Gender Discourses, gender scholar and professor Oyèrónkẹ́ Oyěwùmí offers insights into the repercussions that arise from employing Western frameworks to interpret an African existence, specifically that of the Yoruba people. She states:

Consequently, the promotion in African studies of concepts and theories derived from the Western mode of thought at best makes it difficult to understand African realities. At worse, it hampers our ability to build knowledge about African societies.

Oyèrónkẹ́ Oyěwùmí's perspective necessitates approaching African histories with technology by refraining from the Western mode of thought shaped by capitalism, colonialism, and any other oppressive "-isms" that are at the bedrock of influencing our worldview. These oppressive "-isms" distort our understanding of non-Western realities. Frankly, the Western lens often looks at technology solely as a means to accumulate & hoard capital, when in truth, technology is merely the act of creation and the tools that facilitate the process of making. Technology’s true essence reveals that it is not something that only a few are privy to but rather, it begins with the individual’s capability to imagine.

Tuggar’s Working Woman occupies a liquid space that Minna Salami describes as where African feminism and African futurism meet—a realm where Western understanding is suspended, allowing African disobedience and imagination to claim sovereignty. It is within this realm that any attempt to approach with even a hint of Western influence will inevitably result in one succumbing to the will of water.

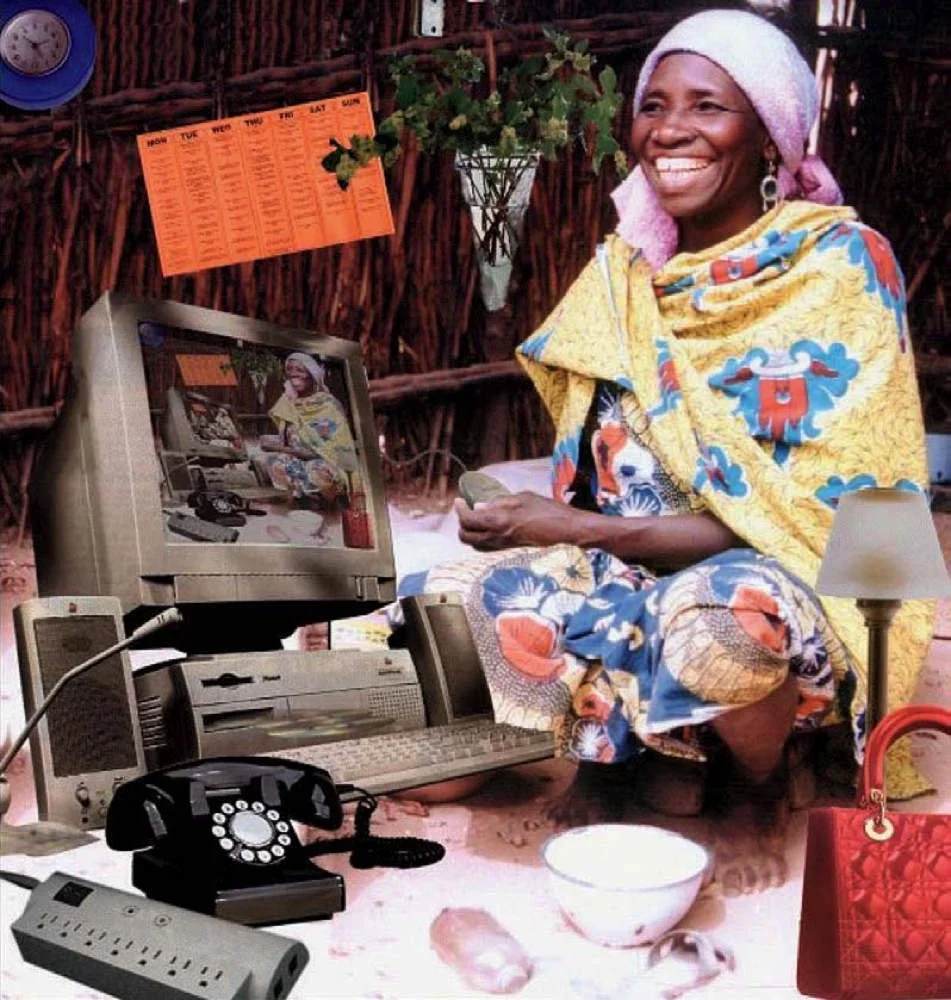

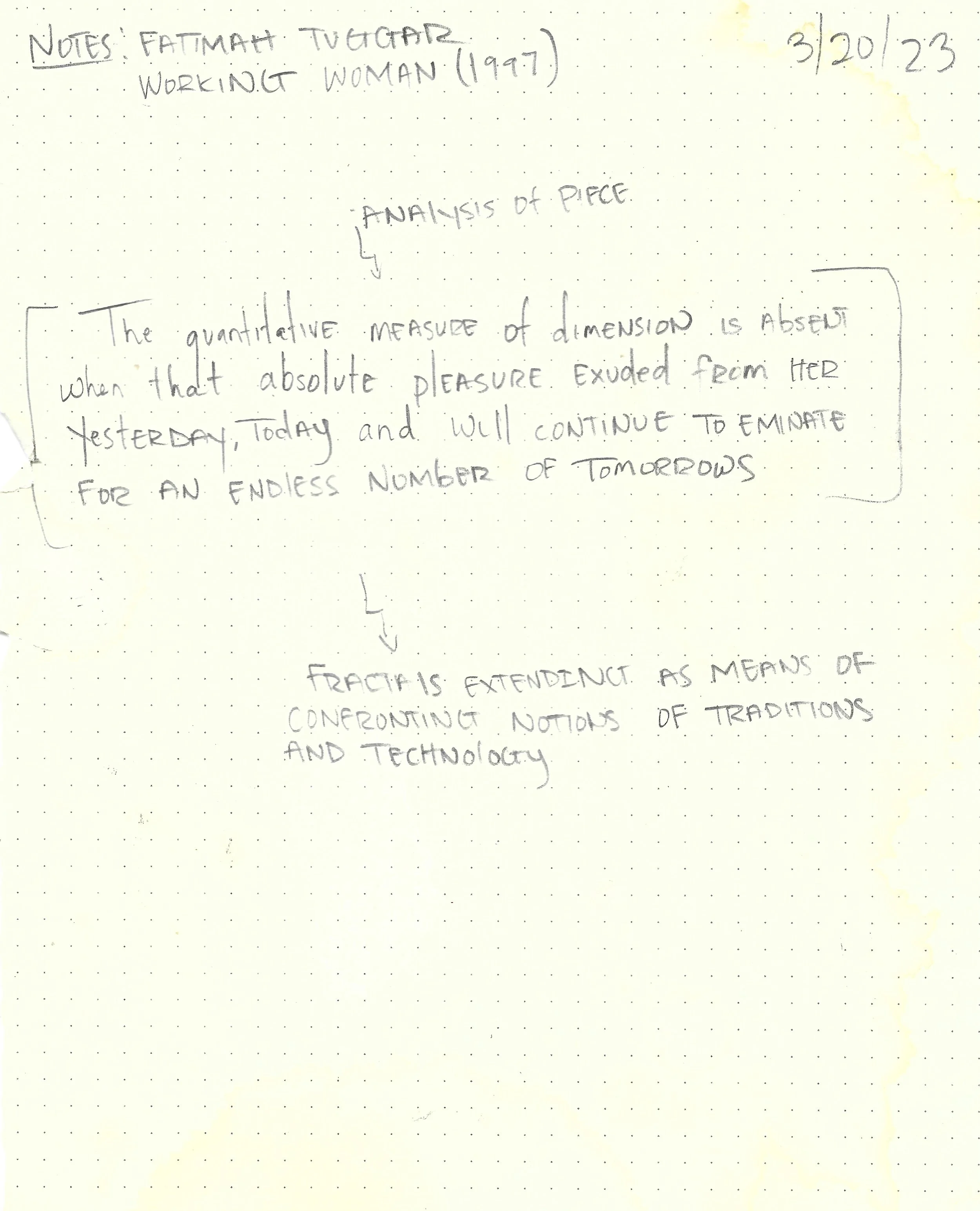

In Working Woman, we witness the interweaving of three parallel narratives, intertwining the realms of time, technology, and examining the role of African femininity. Tuggar imaginatively crafts an image where these entities can exist outside the confines of Western conformity and understanding— Ultimately creating a space of resistance. By employing the use of mise-en-abyme (the act of placing a copy of an image within oneself) displayed on the computer monitor, Tuggar evokes the resonance of fractals found in African architecture and design. This intentional parallelism invites us to think about the ancestral lineage of technology, which, akin to time and African femininity, manifests in a non-linear, self-referential, and cyclical manner. Tuggar's work, rooted in the legacy of ancestral wisdom, embodies the resilience and ingenuity of African cultural traditions and opens us up to expand our ways of engaging and understanding technology.

Fatimah Tuggar Working Woman, 1997 Inkjet print mounted on vinyl 50.75 x 48 x .25 in

Fatimah Tuggar redirects our understanding and collective imagination, by using Photoshop to imbue her images with a sense of playfulness that doubles as a provocative confrontation to her audience. Her method of storytelling resonates with the tradition of Ananse the Spider, a principal character in the folklore of the Black diaspora. Ananse, celebrated for his intelligence, resourcefulness, and cleverness, outsmarts his more physically powerful opponents by employing his trickiness, creativity, and wit. In a similar vein, Tuggar employs her artistry and narrative prowess to challenge dominant narratives and power structures. By subverting notions of image authenticity, she compels viewers to question the very essence of what they perceive. This intentional "fakeness" serves as a powerful critique, drawing focus to the boundaries that Western understanding has imposed upon the audience's capacity for imagination. In doing so, it calls us to interrogate our positions of power as we encounter representations of the Black female body, prompting a necessary reckoning with the pervasive influence of these structures.

In the 90s, computer software like Photoshop offered access to an extended imagination, expanding the boundaries of possibilities for humans. Today, with the invention of compact devices like smartphones and intangible devices like A.I., technology has become so functional to the point it renders invisible. It is at this juncture that Tuggar juxtaposes the societal function of women and the functionality of technology. Both these entities, the woman draped in yellow traditional cloth and the functionality of the computer monitor that is in front of her, are active participants in the continual progress of society. They are indispensable resources that contribute to various aspects of our lives, from caregiving, community building, discovering sustainable practices for environmental stewardship, to facilitating economic growth, enabling education access, and advancing scientific research. Despite their vitality, these entities and their contributions often go unnoticed, seen as mere tools that society imposes its demands upon thereby reducing their existence to surface-level utility.

In contemplating the woman’s presence, swaddled in her vibrant traditional cloth, radiating a captivating smile, and positioned just off-center to the right yet commanding the entirety of the image, we are transported to a place where memories of the dawning sun in the eastern sky are awakened. Paired with this memory echoes the ideas Minna Salami presents in her article The Liquid Space where African Feminism and African Futurism Meet on the liquid nature of time. The woman’s presence encapsulates a metaphor that converges ancestral memories, the awareness of this present moment, and uses an unconstrained imagination as a mechanism to connect to the potential transformations of the future, laying bare the inseparable interconnectedness of these temporal dimensions. Thinking of time as intertwined temporalities challenges our linear understanding of time and makes today just as imperative as tomorrow.

When considering technological advancements of the future, Tuggar’s work uses decolonized imagination as the ultimate teleportation device. With decolonized imagination, we contemplate the limitations of our current reality. Tuggar's Working Woman becomes a light, shining on and beckoning us to envision the new horizons that await us in each new day, each new decade, each new century, each new era. Tuggar reveals the layers of limitation placed on us by Western frameworks which allows us to venture into the uncharted waters of our wildest imaginings.

Guiding Texts

Guiding Texts

Oyěwùmí, Oyèrónké. “Visualizing the Body: WESTERN THEORIES AND AFRICAN SUBJECTS.” The Invention of Women: Making an African Sense of Western Gender Discourses, NED-New edition, University of Minnesota Press, 1997, pp. 1–30.

Salami Minna. The Liquid Space where African Feminism and African Futurism Meet, Gender and Sexuality in African Futurism Vol 2, Feminist Africa, 2021, pp. 90-94.